Resilience

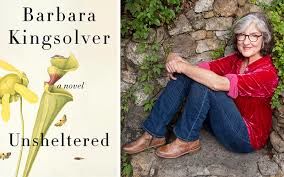

Interview with Barbara Kingsolver: "Unsheltered"

New book offers perspective and hope in tough political times.

Posted November 2, 2018

Barbara Kingsolver has never been one to dance around the issues of our times, and her latest novel is no exception. Unsheltered deftly weaves together two stories, taking place during two turbulent political eras separated by more than a century. While #45 is not mentioned by name, he most definitely is “the billionaire running for president who’s never lifted a finger.” He is the candidate who brags that “he could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody, and people would still vote for him.” He is the eye of the political storm swirling in a country that is frustrated and broken, and turning on each other. Trump is the president pushing the planet toward disaster on every front. And yet…

Unsheltered isn’t an easy read, but it is ultimately hopeful. Kingsolver juxtaposes our current dire situation against the post-Civil War backdrop with the stories of two families living in the same home. Her alternating storytelling structure reminds readers that history is cyclical, and we will survive to see better days. Here’s more from Ms. Kingsolver:

Jennifer Haupt: This novel weaves together two very different time periods with parallel stories that touch on the same themes of tolerance, social disruption, and the difficulties of raising a family in a seemingly crumbling world. What prompted you to use the post-Civil War historical backdrop to contrast with the contemporary backdrop?

Barbara Kingsolver: I wanted to write about how scary it is to give up familiar expectations, even when our old rules no longer apply very well to new times. Humans are such fascinating creatures. In this moment we’re experiencing scarcity and failure of our shelter at so many levels—economic, social, environmental—but we still keep believing more growth and consumption will fix everything. It seems to be the only tool in our kit, so we keep trying.

My novel compares the current crisis with an earlier one, when the US was economically and socially devastated by war, and the news arrived from Charles Darwin that humans are perhaps not the bosses of all life on earth, but in fact subject to natural laws just like all other species. This suggestion brought down the house—not in a good way. People hung Darwin in effigy and rallied around any leader who promised to hold on to the past rather than accept new realities. Times may change, but some aspects of the human psyche never will.

JH: The chapters deftly alternate between two families living in the same house in New Jersey 140 years apart, who navigate uncertainty in all sorts of “brave, sweet and ridiculous ways.” Why did you choose to tackle the political realities that have been escalating since the last election with fiction instead of nonfiction? What can you accomplish with fiction that you can’t with pure journalism?

BK: I began researching and structuring Unsheltered in 2013, thinking to myself: “Wow, this is looking like the end of the world as we know it. How, as a society, are we going to handle this?” I had no idea how relevant that question would become over the next five years. My interest is human behavior, and the complex ways we do or don’t come to terms with ourselves, our societies, and our habitats.

A novel is the form for that kind of exploration, through characters, plot, and language that can spark vivid imagery. Journalism offers facts. A novel invites you inside another human brain. My project here is the latter.

JH: Willa and Thatcher, the two main characters, both find shelter from the madness of the world in their families. How important is family/community to you in keeping your resilience during these difficult times?

BK: Family and community are very important to me, but this novel is not about me. I populated it with characters who really don’t find much shelter in their families—a lot of relationships fall apart. New ones come together in surprising ways.

All the characters are dealing with the double-edged nature of being “sheltered.” It means “safe and sound,” but it also means “naive, unworldly, unprepared for the challenges ahead.” Sometimes resilience may come from letting go rather than holding on.

JH: Tell me more about the theme of “adaptability" in this novel.

BK: History is cyclical and we will ride out this tyrannical government; we will survive.

Adaptability fascinates me—in biology, in societies, and the human psyche--and I do think looking at the past can throw some light on the present. Unfortunately, I can make no promises that we’ll survive. As a novelist, I have no special gift for predicting the future, nor do I see that as my job. My interest is to invite you, as a reader, into an interesting conversation with yourself.

JH: Today, so many of us feel overwhelmed by all of the bad news we’re bombarded with. I constantly hear people saying they can’t even watch/listen to/read the news anymore. How important is it to stay abreast of the news—even when it’s consistently bad and the average person feels powerless?

BK: I would never give anyone personal advice! I expect people will consume news as they see fit. I can only offer, from a biological perspective, that the human brain isn’t well equipped to absorb tragedies at a global level. We evolved in small social groups. Now, with profound technological extensions of the social group, we can learn about thousands of kinds of human damage every day, and we can try to absorb this information intellectually. But as the animals we are, we can only actually feel a few of them at a time. Beyond that, we get badly overextended—powerless as you say. The brain being what it is, we’re best prepared to engage with the joys or miseries of the people we know personally.

This means we end up caring most for our familiars—who often tend to be people a lot like us, living within our same little slice of the world. It’s harder to feel genuine compassion for people who are out there in other places, carrying on utterly different lives. This is why I write novels: to cultivate empathy for the theoretical stranger. A novel is news of the world, delivered at an accessible human scale.

JH: What do you hope readers will take away from this novel that may provide some hope?

BK: The magic of a literary novel is that it isn’t just one thing—it’s a different experience for every reader. What we take away from it is framed by the experience and questions we bring to it. The novels I read in my youth, when I reread them again years later, always land very differently because I’ve become a different person. Anyone is invited to take what he or she wants from Unsheltered. I hope you’ll get absorbed, have a good time, and come out the other side with a satisfaction based on your own nutritional needs as a reader. The one thing I can promise is that it’s not going to leave you in despair. Because I’m me, and that’s not what I do.

Barbara Kingsolver’s books of fiction, poetry and creative nonfiction are widely translated and have won numerous literary awards. She is the founder of the PEN/Bellwether Prize, and in 2000 was awarded the National Humanities Medal, the country’s highest honor for service through the arts. Prior to her writing career, she studied and worked as a biologist. She lives with her husband on a farm in southern Appalachia.